Let’s Hear it for Shame II: Once Upon a Time

“Let’s Hear it for Shame,” a Five Part Series

At the risk of sounding like the old fogey that I am (80 years old, after all), I offer my thoughts on the passing of a key social tool. ?Let?s Hear It For Shame? is the title of this five-part series.

II: Once Upon a Time

Shame used to be seen as a blessing, if only because it could be counted on to keep people in line.

Not so long ago shame was seen in a very different light; it was regarded as a legitimate form of social control. Shame was the punishment for not conforming to the community standards. Men would have been ashamed to violate the dress codes of the day?like the one that required men to wear hats whenever they went outdoors.

Shame would have also come upon families that had seen one of their children run away from home, or families with any whiff of suspicion regarding improper sexual relations within its members. It would have clung to the parents of a youth who had been brought home by a policeman for misdeeds, even if the young man was released at the doorstep of his house.

Shame was the inevitable consequence of misbehavior in school?whether the punishment was a belt whip to the open hand, an order to clean the classroom after school, or a recital of the student?s failures in front of everyone. No scolding or punishment was ever a private matter in those days. A smirking group was always on hand to witness everything. But that was the point, after all: to use shame to rachet up the admonition for reform and to stifle the temptation to disregard it.

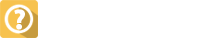

What I remember from my early childhood in Buffalo wasn?t so very different at bottom from the type of social control that kept Pacific Islanders in line, I suppose. Shame was the device used to maintain public order and good behavior. Long before policemen patrolled the streets and prison cells became overcrowded, people were kept in line by fear that they would lose their reputation.

Much the same was true in the islands. Formerly a young man who got into a fight with someone in his village, or who attempted to steal a neighbor?s car or damaged the property of another, would have been reported to the magistrate rather than arrested by the police and hauled away to face criminal charges. The guilty young man, along with his parents, would have been summoned, along with his parents, to account for his deeds in front of the mayor and those he had harmed. The youth would have been required to face the consequences of his actions and his family obliged to make restitution.

Shame was a prime ingredient in resolving such matters in those days. It was also a compelling reason for parents to make sure that their wayward son did not repeat such behavior in the future.

Spouse abuse in the islands

offers another example of the contrast between then and now. When households

were larger and made up of more than just parents and children, a man would

have thought long and hard before screaming at his wife, much less punching

her. For one thing, her blood relatives probably lived not too far away. But in

any case, at the regular family gatherings bruises and black eyes would have

become an instant topic of conversation. At first the woman?s relatives might

have counseled patience with her spouse, but their readiness to let the

incident pass wouldn?t have gone on forever. At some point, they would have

intervened on her behalf.

The forms of this intervention might differ with the culture. In some places, her brother might have had a one-on-one talk, or possibly something more than just a talk, with her offending spouse. If the problem continued, her family might have brought her back to stay with them until her husband learned how to behave properly toward her.

Whatever happened wouldn?t have entailed a quick 911 call leading to a restraint order or perhaps even criminal charges and an arrest. It would have been a process more drawn out, but always under the watchful eye of the woman?s own flesh and blood. Needless to say, throughout the whole process shame would have been a strong motive for behavioral change.