A Gift From Afar

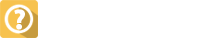

Just three days after Christmas, three travelers from the east (at least if you think of Spain as lying to the east) brought to Guam a gift?the skull of a Jesuit priest who had been killed on the island 330 years earlier. The priest, Fr. Manuel Solorzano, was one of the twelve Jesuits who lost their lives in what have come to be known as the ?Spanish-Chamorro Wars.?

The skull was a reminder of the worst of times, some would say. People died in unprecedented numbers from disease and violence, the culture was radically transformed, and for the first time islanders lived under a foreign flag.

Or were the times blessed despite all this, as others would argue? These were the years of the planting of the faith?something that remains sacred for much of the island population today. But the Spaniards also planted corn, just as they introduced farm animals, new tools, a plentiful supply of iron?everything associated with the rise of modernization in that age.

What the Spaniards (and the Filipinos and Mexicans who accompanied them) brought was a mixed bag, to be sure. Should we celebrate this period of early contact or lament it? I wouldn?t be a Jesuit (as I still am!) unless I was comfortable with the answer, ?both.? After all, we Jesuits admit that we are sinners, but are also called to accompany Christ. If there is this undeniable mix of evil and holiness in our persons, why shouldn?t there be the same mix in the works that we do? Not just back hundreds of years ago, but today as well.

The church on Guam took advantage of this gift?a human skull, bought by descendants of the priest?to apologize for the damage done and to celebrate the real achievements of this time. Perhaps the highpoint of the special mass and the responso that followed was the recitation of a long list of names?Chamorro and Spanish of those who were killed during this period. For a change, the names were recited together?not to support one side?s case against the other, but to commend all to their heavenly father in prayer.

This was intended to be a step toward reconciliation. And it was. At the two roundtable discussions held that week, those who championed the Chamorro activist position shared their passion with the defenders of the mission. Arguments were offered, questioned and discussed. But the purpose of this was not to score points against our rivals. It was to bring a process of healing and move on so that all of us together can carry on our exploration of the past with respect.

So, I think that we can call the skull, brought from afar by three travelers, a real gift for Guam. It may not have been gold, frankincense or myrrh, but it could be far more valuable than these. It might have been the opportunity to begin to heal the divisions in the people of this island.